Creating portraits is one of Felipe Jasso’s passions, and much of his work references Día de los Muertos, a vibrant and deeply meaningful tradition celebrated primarily in Mexico that honours deceased loved ones. This celebration became particularly significant for Jasso after his father’s death. Day of the Death is celebrated every November 1st and 2nd, and coincides with the Catholic observances of All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day. The holiday blends indigenous customs and Catholicism, reflecting the rich cultural tapestry of Mexico. In recent years, Día de los Muertos has transcended religious boundaries and geographical frontiers, with many people around the world adopting the celebration for various reasons.

Jasso’s work honours his culture, and he follows the tradition of seeing Día de los Muertos as a time for families to remember and celebrate the lives of those who have passed away. It is a joyful occasion rather than a sombre one, emphasizing the belief that the deceased return to the world of the living during this time. Families create altars, or ofrendas, in their homes and cemeteries, decorated with photos, favourite foods, drinks, and personal items of the departed. Marigolds, known as cempasúchil, are commonly used to adorn these altars, with their vibrant orange colour and fragrance believed to guide the spirits back home.

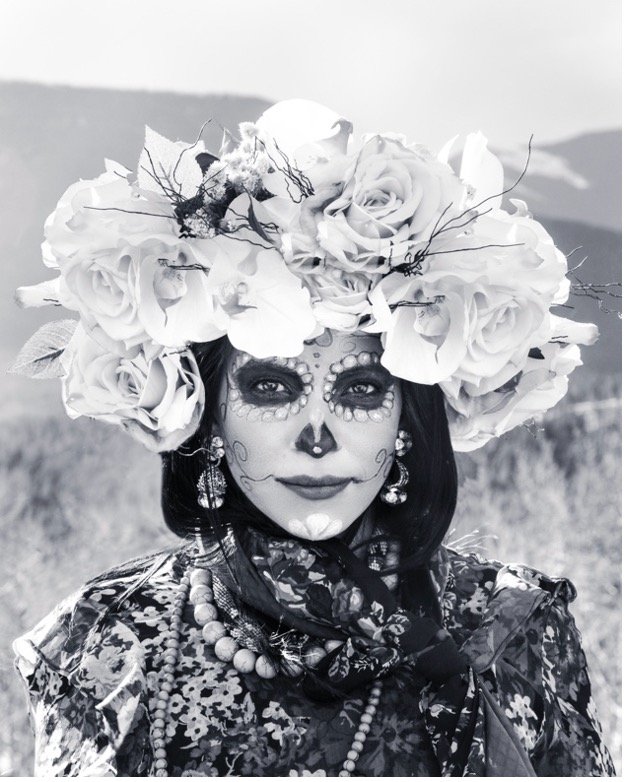

La Catrina is a portrait of a female figure posing in a valley with dramatic natural lighting. She wears traditional garments, a crown of flowers, and Catrina makeup. This portrait was inspired by Jasso’s observation of his mother’s strength and wisdom after his father passed away. The landscape is cold and sombre, contrasting with the vibrant colours of the flowers and the striking resemblance of La Catrina, who stands still, looking directly into the viewer's eyes with a peaceful expression, illuminated by the heavenly natural light that follows a storm.

Jasso expresses that when someone immigrates to a different country, they often become nostalgic. For him, photography is one of the strongest tools to preserve memories and even create new ones that may exist only in someone’s mind; it is a good way to stay close to one’s people. Jasso connects his own experiences and merges his ideas to create his portraits. Using influences of magical realism from his early education, Jasso brings characters to life, sometimes as a way to help himself cope with the distance from his family, as well as the distance from his deceased loved ones.

Beyond Life is a portrait depicting a female and a male figure standing together in a frigid yet calm environment. The long road behind them, marked by the symmetry and perspective of the trees, suggests a long history together. Their elegant and well-kept garments, the flowers, and their bare feet touching the cold surface indicate that this couple is no longer alive, but their love keeps them together, beyond life.

The figure of La Catrina was originally intended as a critique of the upper class. Over the years, La Catrina evolved beyond her satirical origins, becoming a central symbol of Día de los Muertos. Seeing this character as a child was impactful and sparked a special curiosity for Jasso. He remembers waiting to see this character all over the town he grew up during the Day of the Dead celebrations, much like a child waits to see Santa during Christmas. However, the experience wasn’t always easy, as some of the representations were quite dark. Still, it was impossible for the artist to resist wanting to see as many as possible, comparing them and creating his own stories about them.

Portrait of La Catrina is a black-and-white photograph showing a female figure in traditional Mexican clothing, standing in a valley. The main focus of this photo is the eyes, which seem to follow the viewer, creating a deeper connection with the character.

Much of Jasso's work consists of studies of the subconscious. Sometimes the inspiration is not immediately clear to the artist, and often it is during the process that the reason emerges. It is important for the artist to trust the process and continue developing the idea despite feelings of confusion. Additionally, since much of this work takes place outdoors during winter, models also need to be prepared and willing to endure the cold. In the end, the images captured can be quite striking, as they merge the colors of Mexican culture and symbols with the mysterious, beautiful, but cold landscapes of the North—something rare in both cultures.

Waiting is a very personal work created by Jasso, portraying a female Catrina sitting and holding a teacup. She is waiting, but time is running out, with a dark silhouette behind her—like a memory of someone who is no longer present but remains beside her as promised. The landscape is dry and cold, with light reflecting from another world merging into this one.

Día de los Muertos showcases a unique view of death in Mexican culture. Rather than being feared or avoided, death is seen as a natural part of life. This perspective is influenced by ancient Mesoamerican beliefs, where death was viewed as a continuation of the life cycle. The celebration is filled with lively music, dance, and vibrant costumes, often featuring sugar skulls and skeletal figures, which symbolize the playful and humorous aspects of life and death.

La Muerte is a portrait of an androgynous figure wearing a skull mask adorned with a crown of flowers, sitting patiently in the middle of a street in extremely cold weather. The figure looks directly into the viewer's eyes, conveying a sense of knowledge about something we do not yet understand.

Horses are another important symbol in Jasso’s photography, representing death and seen in various cultures and historical contexts, particularly during the Mexican Revolution. In this period, horses symbolized not only the struggle and sacrifices of the revolutionaries but also the inevitability of death in battle. Additionally, in Mexican culture, horses are often associated with traditional celebrations and rituals, which can include references to death and the afterlife. Overall, horses serve as poignant symbols of both the struggle for freedom and the heavy toll of war. Often, the only way to return the bodies of the loved ones was on a horse, trying to find their way home.

Prayers is an image portraying a female figure praying on her knees, while in the background, a male figure begins to interact closely with a black horse symbolizing death. The landscape is cold but calm and beautiful. For Jasso, the meaning of this image is beautiful, as it suggests a natural healing process and comfort after the passing of a loved one.

Jasso’s work is a testament to how, in recent years, Día de los Muertos has gained international recognition, inspiring celebrations worldwide. However, its essence remains rooted in Mexican culture, where it continues to evolve while preserving its core values. For many Mexicans, the holiday is a poignant reminder of the importance of family, memory, and the unbreakable bond between the living and the dead.

Interested in hearing more from Felipe Jasso and other local artists? Head over to our friends at The Scene and discover more great interviews, artist features, and highlights from Calgary’s arts and culture scene.

Felipe Jasso

Felipe Jasso is a Mexican Canadian photographer who graduated from the Alberta University of the Arts. His works are influenced by the magical realism found in Latin literature, surrealism, classical art, and symbolism. He investigates the subconscious, memory and his inner desires. Using symbolism and complex tableaux, Jasso brings to the forefront fragments of his experiences as a kid growing in Mexico, an immigrant, a queer artist, and his negotiations with the Canadian landscape. Jasso is the former director of The Craig Gallery as a student, and currently he is the curator of Pride in Art. He recently joined The Lumian Collective and has shown his work in New York.